Sowing On The Mountain

Wine is a bridge between the two worlds, the living and the dead. Harvest is a story of death, of profound undoing. The grapevines, which began to grow as the Winter faded, opened into the morning of Spring, and pushed forth green shoots, and the shoots opened into leaf and stem, then into flower and tendril. The flowers opened into fruit, and the shoots grew long and the vines became dense and laden with fruit, and the fruit changed from green to black and swelled with juice and grew sweet in the sun — a pinnacle! And one cool morning, the fields thrummed and creaked with the labor of the pickers, the flash of picking knives, the thumping of cluster into bucket, the snap-cracking of canes, the rumbling of truck engines, the fading human voices. Then, in silence, the year was cut off, the season spent, the leaves yellow, fallen, the swarms of starlings crying out for the lost fruit, for the dying sun. It was over. So fast. What had taken such a long time to grow and mature, to become — gone overnight!

—Edmunds St. John Fall Newsletter, 1998

September 24, 2003

The fever has broken, the cooling sea-wind and fog bathe the parched hills. The inundations of harvest have begun to recede. There will be time to exhale.

It was 117 degrees Sunday afternoon, the 21st, when I walked through the long rows of Mourvèdre at Rozet Vineyard, tasting grapes and trying to sense the relative ripeness of the field. Some of the grapes were quite hot.

117 degrees is, in a way, not so different from 102 degrees; as Jerry Reed once put it, “when you’re hot, you’re hot.” Still, I was glad for a good supply of cold water, and for a vehicle with air-conditioning, to which I could retreat for the drive home. This is the kind of heat that calls all the grapes home. I can’t count the number of stories I’ve been seeing and hearing, over the last few days, of winemakers and growers picking everything at once, and of grapes not getting picked because there aren’t enough hours in the day, not enough pickers in the neighborhood, not enough empty tanks in the wineries, and too many good excuses to keep track of them all. (This is in addition to all the grapes that aren’t getting picked because there’s too many grapes.) And some grapes are getting picked far earlier than might normally be expected because sugar levels are so high due to the intense heat. (This phenomenon is not limited to California; the European harvest this year was one of the earliest in anyone’s memory, and featured the same set of problems, due to a horrifically hot Summer.) So, for now, it’s Ally, ally in-free! for the grapes, perfect, half-baked or otherwise. The forecast suggests rain coming soon — not yet clear how much, or for how long. We have, after Thursday, just a few things still hanging, and, of course, we’re hoping if there is rain, that it isn’t much, and passes quickly, to be followed by enough days of warmth to ripen the stragglers.

Harvest is different each year, but it’s never all great, or all terrible. And there’s always something new. It’s never easy, even when things go smoothly (which isn’t all that often).

We’ve gotten some really terrific grapes this year, and a few that weren’t quite as good as we’d hoped they might be. Getting the terrific ones at the moment they became terrific was, largely, a matter of being willing to be in the vineyard again and again, to ensure that the right moment didn’t slip away while I was sitting in some cantina watching a ballgame, and eating ceviche. Which involved driving, again and again, to Paso Robles, Placerville, and points elsewhere, to check grapes, drop off bins, check grapes again, and so on. Between September 4th and September 23rd, I managed to put more than 4,000 miles of California’s highways behind me. The frustrating thing is that the grapes that weren’t quite as good as we’d hoped they’d be came from vineyards I was in just as often as all the others.

I wondered, a few weeks back “what kind of harvest will this be?,” and I guess I know more now than when the question first arose. Harvest is a powerful experience that lights up some pretty ancient circuits in the human wiring diagram, and, as such, offers metaphorical possibilities that pack some muscle. (Some muscles are better than others, these days; just ask me.) It’s a time of sudden, near-cataclysmic change. Wind features prominently in harvest, and wind is the element in traditional Chinese medical philosophy that embodies change.

The reason I know that last bit of information is that my oldest, (first-born) daughter has just completed her course of study in Chinese medicine and Acupuncture, and has passed her licensing exams, about which I am very, very proud. That’s not the best news, though. On my birthday, a few weeks ago, she found out that, come Spring 2004, she will bring forth her own first-born child, and I couldn’t be more thrilled!

Balancing this joyfulness was the sudden passing, just days ago, of my mother’s first cousin, a sort of second mother to me, in her way, and the last of her generation to whom I had a close connection. She took a chance on me once or twice when I felt all alone in the Universe, and gave me something to hang onto, and I’m sorry I’ll not share her company again. But she’s in my heart now, as I was in hers, back when it seemed there weren’t enough hearts to go around.

So, for whatever else it may be, harvest is a matter of life and death. And wine, among all the variety of growing things that we humans harvest, can be said to occupy both realms. It is quite literally living matter transformed through the death of that matter into spirit. Small wonder it inspires so many, in ways we probably don’t often think about.

I remember, from the first days of my enchantment with wine, the way that simply smelling a really good wine gave me, besides the obvious pleasure to my nose, a sense of being profoundly grateful to be alive, a sense that life in this body is a miraculous gift. I don’t remember the wise person’s name (maybe it was Benjamin Franklin?) who said, “Wine is proof that God loves us.”

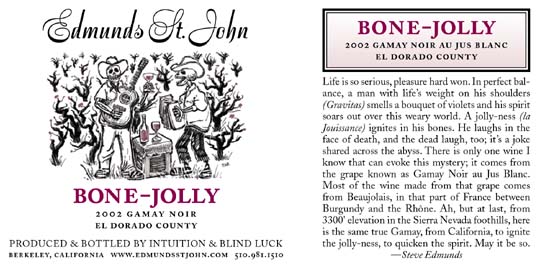

Of course there are many kinds of wine, and many kinds of really good wine, and not all really good wines provoke quite the same reaction, but there is one kind of wine that I have found so irresistibly seductive, that I can’t imagine anyone could fail to experience that lovely sense of being blessed by the opportunity to taste it. (A kind of Wine Epiphany for Dummies, perhaps) Really good Beaujolais, from a producer devoted to his craft, was the wine, back then, that made me feel I’d just been kissed by the girl I had a crush on when I was 15. After a half a glass I wanted to take my clothes off. I felt jolly, right down to my bones. Gamay, the grape responsible for such a wine, does not, successfully, make big, blockbuster wines that critics and collectors take seriously. It’s meant to be relatively light, very fresh, and, at its best, pretty and perfumed.

I’ve always wanted to produce such a wine, but until a couple of years ago, there wasn’t any real Gamay in California from which to make such a wine. Then, after a kind of three way conversation between myself, Ron Mansfield (who farms the Wylie and Fenaughty Vineyards, from which one of our best Syrah wines come), and Bob Witters, about the possibility of establishing a planting of Gamay, things came together, the vines went into the ground, and, in 2002 we brought in the first fruits of their labors and vinified Gamay, grown at 3400 feet elevation in the Sierra Nevada foothills, above the town of Camino, in El Dorado County. Bob Witters’ property is known as Crystal Springs Vineyard, so that name will, in subsequent vintages, appear on the label.

But the name that’s stuck with me for this wine is the one we’ve given it on the label: “Bone-Jolly.” And now the time has come to share that label with the World. The wine will receive its labels over the next week, or so, and we’ll begin shipping it right after that. There isn’t much of it, but I think you’re going to like it. (For more details on the wine, check out its page on our website.)

Autumn Day

Lord; it is time. The huge summer has gone by.

Now overlap the sundials with your shadows,

and on the meadows let the wind go free.Command the fruits to swell on tree and vine;

grant them a few more warm, transparent days,

urge them on to fulfillment then, and press

the final sweetness into the heavy wine.Whoever has no house now, will never have one.

Whoever is alone will stay alone,

will sit, read, write long letters through the evening,

and wander on the boulevards, up and down,

restlessly, while the dry leaves are blowing.–Rainer Maria Rilke (translated by Stephen Mitchell)

after the Summer, there’s nothin the wind doesn’t own.

–Steve Edmunds (After the Summer, 2000)